The Ambitious Mission of the Mouse-Free Marion Project

Our recent Marine Evening welcomed guest speaker, Dr Anton Wolfaardt, Project Manager of the Mouse-Free Marion Project, who presented a powerful vision for Marion Island—a South African sub-Antarctic treasure—united by a common goal: to restore its ecosystem by eradicating invasive house mice. This ambitious conservation initiative aims to address the devastating impact of these non-native rodents on the island’s fragile ecosystem and to protect Marion’s unique seabird populations from local extinction.

Wandering Albatrosses on Marion Island

A Brief History of Marion Island and the Mouse Invasion

Located in the remote Southern Ocean, Marion Island and its sister island, Prince Edward, are part of South Africa’s only overseas territory and serve as one of the country’s Special Nature Reserves. Discovered in the late 18th century, Marion Island remained relatively untouched until the 19th century, when sealers began to frequent it. With them came stowaways—the first house mice, likely introduced accidentally in the early 1800s. For decades, these mice managed to survive in the harsh conditions by feeding on invertebrates and native plant seeds, but as the climate grew warmer and drier, their population increased substantially.

Over time, the mice depleted Marion Island’s natural invertebrate populations and began to prey on the island’s seabird colonies, including the globally significant wandering albatross. Today, Marion Island is home to some of the world’s largest colonies of seabirds, yet these birds have no natural defences against mammalian predators, making them vulnerable to invasive mice.

In the absence of natural predators, the mice population exploded, and by the early 2000s, a worrying shift in behaviour was observed: mice began attacking seabird chicks and even adult birds, gnawing on them alive. The resulting predation poses an existential threat to Marion Island’s seabirds, with scientists estimating that nearly 19 of the island’s 29 bird species could face extinction if no action is taken.

The Ecological Significance of Marion Island

Marion Island is a critical biodiversity hotspot in the Southern Ocean. As one of the few sub-Antarctic islands, it provides essential breeding grounds for large seabird populations and is home to four species of penguins, numerous albatrosses, petrels, and skuas, among others. The wandering albatross, for instance, relies on Marion Island for over 25% of its global breeding population. Marion also hosts two species of fur seals and significant populations of sub-Antarctic elephant seals, as well as a thriving marine ecosystem that includes orcas and other marine mammals.

The isolated location and minimal human activity initially helped Marion Island maintain its biodiversity. However, the introduced house mice are eroding its ecological integrity by disrupting nutrient cycles and preying on native species. The need for swift and effective conservation action is urgent, as unchecked mouse predation could lead to irreversible damage, impacting not only Marion Island but global biodiversity.

Learning from Success: Eradication on Other Islands

The Mouse-Free Marion Project draws upon the experiences of other island conservation efforts. Notable examples include the successful eradication of invasive rodents on South Georgia, Antipodes, and Macquarie islands. Each of these islands faced similar ecological threats and used innovative strategies, such as aerial baiting, to eradicate invasive rodents.

- South Georgia Island: This British island, significantly larger than Marion, was plagued by rats and mice that decimated seabird populations. Through phased aerial baiting campaigns, conservationists successfully eliminated the invasive species, allowing seabird populations to recover. South Georgia’s success set a precedent for large-scale eradications on remote islands with challenging terrain.

- Antipodes Island: In New Zealand, Antipodes Island is home to numerous seabird species that were threatened by rodents. An aerial baiting program there successfully removed mice from the island, providing a model for Marion Island’s baiting operations.

- Macquarie Island: Located between Australia and Antarctica, Macquarie Island’s efforts combined aerial and manual baiting techniques to achieve eradication. This campaign was successful in removing rats, rabbits, and mice, leading to a substantial recovery of native vegetation and bird populations.

These successes demonstrated the effectiveness of aerial baiting in large-scale rodent eradication and provide valuable insights into the planning and precision required for Marion Island’s operation.

The Mouse-Free Marion Project: An Ambitious Plan

The Mouse-Free Marion Project is preparing for one of the most challenging eradication operations in conservation history. Scheduled for the winter season, when seabird breeding is at a low point, the project plans to employ aerial baiting—using helicopters to systematically distribute rodenticide bait across the island’s 30,000-hectare terrain. Precision is essential; the baiting must be thorough, with no gaps, to ensure that all mice are eradicated. Even a single pregnant mouse surviving the baiting could repopulate the island.

The team is implementing cutting-edge GIS and GPS tracking technology to monitor bait coverage, ensuring overlapping swaths that minimize any potential gaps. Skilled pilots trained in island eradication techniques will be central to the operation’s success, navigating complex flight paths over Marion Island’s rugged topography. The entire process is expected to be conducted in a narrow window of time, with every aspect meticulously planned to optimize coverage and prevent bait wastage.

Dr Wolfaardt acknowledged the inherent risks of the operation, including potential impacts on non-target species. However, he emphasized that rigorous studies and planning have gone into selecting bait that is effective against mice but minimizes harm to other wildlife. The bait must also be weather-resistant to remain effective during the island’s rainy winter months.

Ecological Benefits and the Hope for Recovery

If successful, the Mouse-Free Marion Project could bring transformative ecological benefits. Removing the invasive mice would enable seabirds, such as the wandering and grey-headed albatrosses, to nest safely, free from predation. This would also allow native invertebrates, crucial for nutrient cycling, to recover, restoring the island’s ecological balance.

Island eradications have consistently shown that ecosystems can be remarkably resilient when freed from invasive predators. Following rodent eradications on other islands, native bird populations rebounded significantly, and entire ecosystems began to regenerate. The Mouse-Free Marion Project aims to replicate this success on a larger scale, demonstrating that even the most daunting ecological challenges can be addressed through science-driven conservation efforts.

Global Impact and the Future of Island Conservation

Beyond Marion Island, this project holds significant global implications for island conservation. Islands are disproportionately affected by invasive species, accounting for the majority of recent extinctions worldwide. Successful eradications like the one planned for Marion provide a model for other threatened island ecosystems, underscoring the importance of proactive conservation measures.

Dr Wolfaardt emphasized the urgency of this work, not only for Marion Island but for the future of biodiversity conservation worldwide. He noted that removing invasive species, though challenging, addresses a tractable threat, making native species more resilient to other pressures such as climate change and habitat loss. By safeguarding Marion Island’s ecosystem, the project helps protect biodiversity on a global scale, contributing to conservation knowledge and showcasing South Africa’s commitment to environmental stewardship.

As preparations continue, the Mouse-Free Marion Project inspires hope for a future where Marion Island’s unique ecosystem can thrive once again. For conservationists and nature enthusiasts alike, it stands as a reminder of the resilience of nature and the profound impact that focused, science-based efforts can achieve.

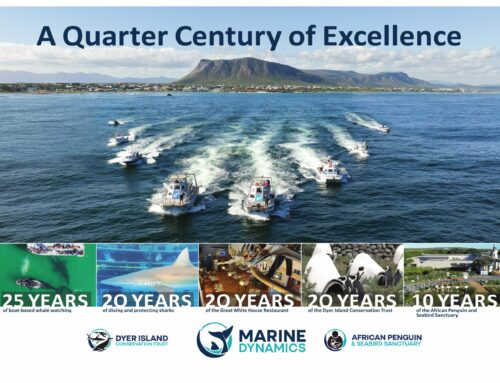

The 2024 Marine Evening series concluded with a captivating presentation by Dr Anton Wolfaardt, Project Manager of the Mouse Free Marion Project. Hosted by the Dyer Island Conservation Trust and sponsored by Marine Dynamics Shark & Whale Tours, Marine Dynamics Academy, and the Great White House, the event drew an enthusiastic crowd, eager to learn about the project’s conservation efforts. Dr Wolfaardt’s insights into protecting Marion Island’s unique ecosystem left a lasting impact on all attendees.

With the 2024 season now wrapped up, Marine Evenings will take a short break, resuming in February 2024 with a new lineup of inspiring talks and community events. Don’t miss out on next year’s sessions—sign up here to join our Marine Evening mailing list.

Dr Anton Wolfaardt, Project Manager of the Mouse-free Marion Project and Wilfred Chivel, CEO of Marine Dynamics and Founder of the Dyer Island Conservation Trust.