~ This is a joint blog post between SeaSearch and the Dyer Island Conservation Trust

With less than 500 individuals estimated to be left in South Africa, team members from The SWORD Project (Signature Whistle Occurrence, Recapture and Density) of SeaSearch visited Kleinbaai to work with the Dyer Island Conservation Trust (DICT) to test new acoustic equipment and record humpback dolphin vocalisations. These organisations are part of The SouSA Consortium, a group of researchers and conservationists working together to research and conserve the endangered humpback dolphin in South African waters. In 2017, work by The SouSa Consortium individually identified 247 animals around South Africa, collated from photo ID data from around the country spanning a 16 year period, including data from DICT in Kleinbaai. However, continued research on this species is made difficult due to their extreme coastal habitat. Researchers often struggle to photograph these animals because of their shy nature and occurrence in the surf zone and so The SWORD project is currently looking towards acoustic methodologies where they can more easily and safely record humpback dolphins.

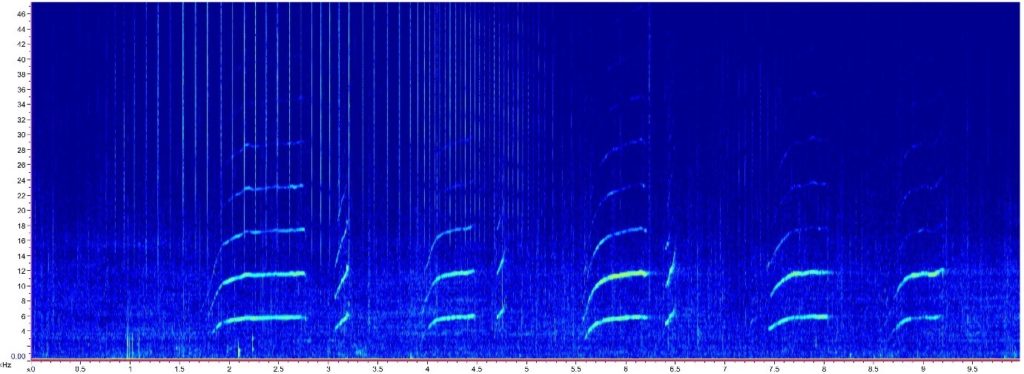

The acoustic methods the team are using are all based on dolphin whistles. From birth, dolphins produce high pitched whistles. Each dolphin uses its own whistle contour when communicating with other dolphins and in this way they act somewhat like a name in human society. These whistles, called ‘signature whistles’ remain very stable over time – so that dolphins recorded decades apart are found to use exactly the same whistle contour. Dolphins have been shown to recognize each other’s signature whistle for a similarly long period of time.

Dolphin whistles are recognizable audio-patterns that can be captured using underwater hydrophone-equipment. Scientists from SeaSearch are planning widespread passive acoustic monitoring along the coast of South Africa to monitor this population of humpback dolphins. By eaves dropping in on the signature whistles produced by wild dolphins, the team will document where and when individual dolphins are in space and time. From these data they will determine dolphin density (the number of individuals per unit of area) and how far individuals range along the coastline, which can in turn be used as important conservation tools. Our current acoustic knowledge on humpback dolphins in South Africa is limited and these populations are threatened by human activities including noise pollution, overfishing, boat interactions, shark nets, and coastal construction. Therefore, these data collected will be invaluable to inform conservation action and management options allowing for their improved protection. Several studies have documented signature whistle use in humpback dolphin species. However, there are no published reports of the acoustic behaviour of our study species, S. plumbea, in South Africa. Pilot data from SeaSearch provides strong evidence for signature whistle use, from which a first catalogue of signature whistles has already been generated. This new method of individual monitoring using signature whistles is a cost effective and low impact method for studying endangered dolphins. The work in Kleinbaai, marks the early stage in testing these new and exciting acoustic methods in humpback dolphins.

While the deployment went very easy, the retrieval had a slight complication as it turned out someone had cut the buoy loose which we would have used to retrieve the recorders. Luckily a quick dive by one of the crew helped locate the mooring with the equipment still attached and allowed us to pull everything back on board. During this field work the team were also lucky to encounter a group of humpback dolphins. They successfully identified individuals through Photo-ID and several were previously identified individuals in our catalogue. One of the individuals we saw is Captain Hook, one of the better known humpback dolphins in the greater Dyer Island area as we encounter her on a regular basis. Her name originates from her unique hook like dorsal fin. She always shows relaxed and calm behaviour around the local eco-tour vessel even when she is with a calf, and we know two of her calves already and hoping there will be more in future. The acoustic recordings were successful with several dolphin encounters detected throughout the deployment. The large volume of data is already being processed by our specially designed species classifiers which will aid in identifying specific species of vocalising dolphin.

This fieldwork was a great example of different organizations collaborating together to ensure the collection of valuable data on an endangered species. Further, this allows for sharing of vital information and understanding of the species, which in turn will aid conservation actions and management decisions. Understanding signature whistle allows us to track these animals and find out how they use certain areas in the marine environment even when we’re not around.

PhD candidate Sasha Dines observing humpback dolphins in Kleinbaai during equipment retrieval (photo credit: Ralph Watson, DICT).

PhD candidate Sasha Dines observing humpback dolphins in Kleinbaai during equipment retrieval (photo credit: Ralph Watson, DICT).

Humpback dolphins (photo credit: Bridget James, SeaSearch)

Humpback dolphins (photo credit: Bridget James, SeaSearch)

Spectrogram of a humpback dolphin stereotyped whistle (photo credit: SeaSearch)

Spectrogram of a humpback dolphin stereotyped whistle (photo credit: SeaSearch)

Underwater recording equipment recovered by SeaSearch team – including the lost buoy from our mooring! (photo credit: Sasha Dines, SeaSearch)

Underwater recording equipment recovered by SeaSearch team – including the lost buoy from our mooring! (photo credit: Sasha Dines, SeaSearch)

For more information on this research project and humpback dolphin work in South Africa, take a look at the short film “The Sound of Hope” which is available now on YouTube